Mike Lord

4th generation Santa Fe Gringo.

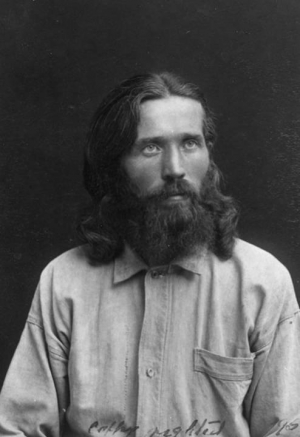

Francis Schlatter, The Healer

Healer and the Cross

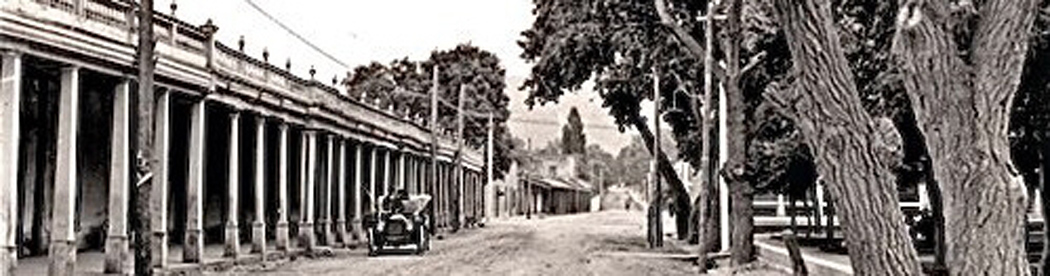

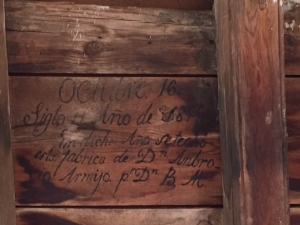

Don Ambrosio Armijo's Roof - By Paula Vallejos

“October 16. The century and year of 1898 (?) this roof was built by Don Ambrosio Armijo.”

If you’ve never seen this before it’s in Albuquerque's Old Town, just before you go into the Gorilla Graphix store. Look up. It’s very cool.

Don Francisco, the interpreter - by Chris Baca

Storytelling Time

When I was a little kid, maybe 5-7 years old, my father would entertain the family after supper by telling us stories of his growing up years in Las Nutrias. We’d sit around in the kitchen table after it had been cleaned up and and listen to him spin his tales. Usually, he’d be sipping a cup of coffee and was totally relaxed. The kitchen would be nice and warm because the old stove was still giving out heat from the lleña that had helped cook my mom’s delicious meal including freshly rolled tortillas. The yummy smells of the recent meal still lingered in the air.

In between sips of coffee he would begin the story. My favorite one was about a pompous villager who would like to lord his command of the English language over the less capable English speakers from Las Nutrias. This must have been around 1910 or so. In those days few people spoke English as Spanish had been spoken in the area since the late 1600s. The area had been settled after the reconquista of New Mexico. In any case, Don Francisco (the “smartest man” in the community) would strut around the village blurting out phrases in

English and asking “Saben lo que yo dije?” “Do you know what I just said?” Of course, no one did. They would shake their heads “No!” He would snort out “Pues es porque yo se mas que ustedes.” “Well, it’s because I know more than you do.” He would strut away with his chin in the air having once again asserted his superior knowledge over the commoners of the little village.

Well, one day, one of the revered elders of the village, Don Tomas Baca, got ill and the curanderas weren’t able to cure him. So it was decided that he had to be taken to the town of Belen to see the only doctor in the area. The young doctor only spoke English. This was about 15 miles away and he had to be driven there in a buckboard. Don Francisco, the most “competent” English speaker, was assigned to go with Don Tomas to interpret for him.

Once they got there Don Tomas began to be examined by the doctor and Don Francisco has to explain to the patient and doctor what was being said. “What are your symptoms?” “Tengo un dolor aquí,”. and pointed to his stomach. “I have a pain here.” Except Don Francisco interpreted “dolor” or “pain” as “dollar”. The doctor was astonished “He has a dollar there?” Yes, nodded Don Francisco. “Did he swallow a coin?” “El médico quiere saber si usted se comió una dolar de plata?” Don Tomas was confused “Este médico no sabe

nada. Esta loco! Que tipo de medico es este? De caballos?” “This doctor doesn’t know anything. He’s crazy! What is he? A horse doctor?” The doctor continued his examination and told Don Francisco to tell Don Tomas to take off his clothes. The old man was hesitant but he was in a lot of pain so he disrobed and the doctor began poking and probing still wondering why Don Tomas had swallowed a silver dollar. He worked his way down to his nether region and told him he was going to check for a hernia and needed to check his groin. “El médico piensa que tiene algo mal con sus huevos!” Don Tomas was frantic. What could possibly be wrong with his balls. Yes, they had shriveled a bit with age but they were quite functional in his mind. However, because he was in such pain he conceded to the request and the doctor asked Don Francisco to tell Don Tomas to turn his head and cough. “Que me está diciendo? No quiero que me toque los huevos!” “What is he saying? I don’t want him to touch my balls!” Don Francisco misinterprets cough as coffee so he says “Se me hace que le dice que toma mucho café!” “I think the doctor is telling you that you drink too much coffee.

Apparently, he can tell your drinking too much coffee by the weight of your balls!”

By then we were all laughing, tears rolling down our eyes. My dad would end the story by saying “Se le acabó el Ingles a ese pendejo, Don Francisco!” In essence “Don Francisco, the dumb ass, ran out of English!”

Obviously the pompous Don Francisco got his comeuppance when he got back to the village somewhat chagrined that he wasn’t as fluent in English as he thought. And Don Tomas was angry because he had been “manhandled” and couldn’t drink coffee anymore.

Story telling was and is an art form. My dad was an awesome story teller. We didn’t have a radio or TV so he was our entertainment.

Albuquerque Metro area was once home to Apaches

Metro area was once home to Apaches

By Dennis Herrick / Rio Rancho Author

Sunday, August 25th, 2019

Most Albuquerque-area residents know about Pueblo Indians. But what about the Faraon Apaches, whose base for many years was the Sandia and Manzano mountains?

Since the late 1590s, Spaniards called the Apaches of the Middle Rio Grande by the Spanish word “faraón” for pharaoh, a reference to Biblical Egyptians. Spaniards reported that the Faraon Apaches were allied with several pueblos against Spanish rule in 1692.

The new Spanish presence had disrupted much of the area’s traditional trading network, resulting in Faraones intensifying raid-and-trade at pueblos to obtain what they wanted or needed.

For Apaches too poor to buy horses – which were forbidden to them, anyway – the alternative was to steal them from Spanish herds at ranches and pueblos.

Most Albuquerque-area residents know about Pueblo Indians. But what about the Faraon Apaches, whose base for many years was the Sandia and Manzano mountains?

Since the late 1590s, Spaniards called the Apaches of the Middle Rio Grande by the Spanish word “faraón” for pharaoh, a reference to Biblical Egyptians. Spaniards reported that the Faraon Apaches were allied with several pueblos against Spanish rule in 1692.

The new Spanish presence had disrupted much of the area’s traditional trading network, resulting in Faraones intensifying raid-and-trade at pueblos to obtain what they wanted or needed.

For Apaches too poor to buy horses – which were forbidden to them, anyway – the alternative was to steal them from Spanish herds at ranches and pueblos.

Spaniards and their Pueblo allies would deploy numerous campaigns against Faraon Apaches to punish them for thefts of horses and other livestock. One of the campaigns came after Faraon Apaches raided settlers around Bernalillo and Alameda.

Historian John L. Kessell wrote about how a campaign launched in 1704 would end with the death of Diego de Vargas, who had reconquered pueblo country after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Vargas led the punitive expedition, marching south from Santa Fe to Alameda with Spaniards and Puebloan allies. The force found Faraones with stolen livestock at the “watering place of Carnué,” which was how Tijeras Pass was known then, but the Faraones escaped. Vargas and several expedition members became ill, and Vargas was taken to a Bernalillo home, where he died at the age of 60.

In June 1706, the year of Albuquerque’s founding, the new villa’s first alcalde mayor, Martin Hurtado, wrote about a visit by “the pagan Indians of the Faraon Apache nation.” Hurtado reported that Faraones “have constantly come to trade and barter with the Spanish inhabitants of the said Villa of Alburquerque (sic) and the Christian Indians of the mountain passes and towns of this district.”

Spanish Gov. Francisco Cuerbo y Valdés had predicted troubles with these same Apaches when he founded the villa, writing: “For (colonists’) security, I decided that a group of 10 soldiers of this presidio should go in a squad, taking their families to escort and guard them, because (the place) is in the main frontier of the barbarous … Faraones.”

Pecos Pueblo residents told Gov. Juan Ignacio Flores Mogollón in 1714 that Faraones “make their base in the Sierra de Sandia from which they sally forth to rob horses and cattle” from pueblos and colonial ranches. Two days later, Faraones took the horse herd at Picuris Pueblo.

Gov. Mogollón reacted by ordering a campaign against Faraones near Bernalillo and Albuquerque, where Vargas had gone 11 years earlier. The force set out in 1715 and searched for weeks without finding any Faraones. It was suspected that someone had warned the Apaches.

As late as 1754, Gov. Tomás Vélez Cachupín noted that raids by one or another Apache band posed a threat to ranches and pueblos around Bernalillo and Albuquerque. By then, the area was also suffering from deadly attacks by Comanches on horseback from the Great Plains.

Author and former Journal reporter Sherry Robinson said some mid-1800s maps still labeled the area from Sandia Mountain to the Pecos River as Faraon territory, although the Faraon Apaches seem to have merged with the Mescaleros by then.

Although on every colonist’s mind in the 1600s and 1700s, today’s memories of the Faraon Apaches of the Sandia and Manzano mountains have faded to obscurity.

Dennis Herrick is author of “Winter of the Metal People” and “Faded Pueblos of the Tiguex War.”

Enchilada Recipe - 1877

I recently came across this recipe from Buckeye Cookery by Estelle Woods Wilcox, dated 1877. I'm assuming that she was from Ohio (The Buckeye State.) It may be that she took a trip to the southwest and observed the preparation of tortillas and red chile by a local cook, recording the process. According to some local Hispanic cooks, she was quite accurate.

ENCHILADAS.

Put four pounds of corn in a vessel with four ounces lime, or in a preparation of lye; boil with water till the hull comes off, then wash the corn (usually done by Mexicans on a scalloped stone made for grinding corn as was practiced by Rebecca), bake the meal in small cakes called "tortillas," then fry in lard; take some red pepper ground called "chili colorad," mix with it sweet oil and vinegar, and boil together. This makes a sauce into which dip the tortillas, then break in small pieces cheese and onions, and sprinkle on top the tortillas, "enchiladas" is the result. Any one who has ever been in a Spanish-speaking country will recognize this as one of the national dishes, as much as the pumpkin pie is a New England specialty.

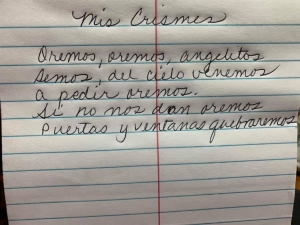

An Old Fashioned Hispanic Christmas - Victoria Martinez

Mis Oremos and Mis Crismas, are holiday traditions that are unique to the villages of Southern Colorado and Northern New Mexico. In the Sangre de Cristo National Heritage Area, the Culebra Villages outside of San Luis have carried on these cultural traditions. For the second year in a row San Luis, the oldest town in Colorado, is bringing this tradition back into their community.

Richard de Olivas y Cordova, active member of the governance team for Adelante San Luis who leads the revitalization of Manito Culture, explained, “The town of San Luis is reviving this tradition as a way for families to come together and celebrate heritage and community.” Although, not held on the traditional date of Christmas Eve (this year’s gather took place this past Saturday, it is still just as powerful a bringing together people. “A family from Texas was passing through town and saw the large gathering of people outside the town hall. They stopped and asked about what was going on, and were just amazed because they had never seen anything like it. We invited them to join and they did, they had a great time, and we hope more people feel welcome to come experience this tradition with us next year.”

“Costilla County Prevention Partners(CCPP) brought students down to be a part of the celebration that had never experienced this tradition. They were just so excited and had so much fun learning and participating in this cultural experience. The resident team of volunteers worked very hard planning and leading this event. ” Said Jessica-Ortega-Dugan, Coordinator of Adelante San Luis.

“This was a great success and partnership for our second annual Mis Crismas Celebration between Adelante San Luis, CCPP, the Town of San Luis and Social Services.”

It begins in each village with the lighting of one luminaria (bonfire) on Dec 16th. On the 17th two luminarias are lit. On the 18th three, so that on the 24th there will be 9 luminarias in each village. On the evening of the 24th, Christmas Eve, a few of the older teenagers don masks and costumes as not to be recognized. They are called abuelos (grandfathers). They make the younger kids sing, march in formation, etcetera-all to the beat of a chicote (a horse whip) around the bonfires. Finally the whole group goes to the homes of their neighbors in the villages to ask for Oremos. In front of the homes the farolitos (candles in bags) are lit. At each door the children, guided by the abuelos, recite this poem:

“Oremos, oremos Angelitos semos.

Del cielo venemos a pedir oremos.

Si no nos dan oremos

Puertas y ventanas quebraremos.”

English Translation:

“We pray, we pray. We are little angels.

From heaven we come to ask for oremos.

If you do not give us oremos,

Doors and windows will be broken.”

Rita Martinez, of San Luis, remembers the tradition from her childhood fondly, “It is a little bit like Halloween. We would put on tons of clothes and gloves to walk through piles and piles of snow on Christmas eve saying Oremos at each house and collecting goodies like empanaditas, biscochitos and candies. Then again Christmas morning we would bundle up again. All the neighborhood kids would all wait outside excitedly for the kids to gather and we would go house to house together saying “Mis Crismas” in place of Oremos. The neighbors all wanted to be the house that had the best goodies and would fill our pillowcases to the top. We would do this all morning, playing in the snow along the way, making snow angels and having so much fun. When we got home, Christmas dinner was ready.”

These festivities are held around Christmas time and relate to Christian tradition, but parts are reminiscent of Judaism and of the Matachina dancers. Richard explains, “The luminarias are lit, increasing by one fire a day, similar to the lighting of the candles on Hanukkah. It is possible this was a way that people could have secretly celebrated Judaism in this area, without being questioned, since they tied it into Christmas tradition. Occasionally the lighting of the luminarias corresponds exactly to the nights of Hanukkah.” The Matachina dancers were originally brought over from Spain, the music and dance depicts the coming together of the Christians and the Moores. The Spanish showed the Native Americans this dance and they adapted it to celebrate the coming together they were similarly experiencing. Costumes and masks were worn and the abuelos used a chicote whip to keep time to the music. “I think it is interesting that the traditional Matachinas have died away, they used to dance and celebrate every Christmas when I was young. Now you can only find them in a few places like Bernadillo, NM. The Abuelos of Oremos is one way that we have kept the connection to that part of our history.”

A Basque Family in America

This 1916 photo is of my great-grandmother on my mother's side, Graceus Marie Inda, and her family. Graceus Tahista came to America in the late 1800s at age 18 from her home in Aldudes, France. She was to marry John Inda, a Basque man 20 years her senior, whom she had never met. Arriving in New York, speaking only French and Basque, she boarded a train and traveled to her new home in Los Angeles. She raised six children, one of whom was my grandmother, Mary Grace. I never knew her, but I know that she was a very tough and determined woman because both my grandmother and mother were.

My mother Grace was born and raised in Los Angeles. She met DeForest Lord, a Santa Fe native, during WWII when he was attending dental school at USC. They married in 1944, and in 1946 she came to Santa Fe, where she raised five children and spent the rest of her life.

On a side note, my great-grandmother was named Graceus Marie, my grandmother's name was Mary Grace, and my mother's name was Grace Mary. This naming tradition of daughters in my mom's family is very old and goes back for generations.

Tesuque Pueblo Boy Buffalo Dancers, 1931

Tesuque Pueblo boys Pete, Tim, Paul, and Clyde Vigil preparing for the Buffalo Dance. During the depression, Tesuque Pueblo dancers travelled to different venues throughout the southwest to perform for tourists. Times were hard and people did what they could to make ends meet.

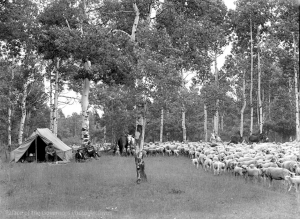

Basque Sheep Herders in New Mexico

Many of the northern New Mexico sheepherders were Basque. They seemed to have no problem with the months of isolation and always had a dog or two for sheep control and company. Near the top of the trail from Cuba to San Pedro Parks there are a large number of aspen trees with Basque carvings (some pornographic) which was one way these guys occupied their time.

About 25 years ago, Kathy, a close female friend, and I backpacked into a high mountain lake near Platoro, Colorado. Shortly after establishing our camp, a Basque sheepherder, his flock, and his dogs set up camp on the other side of the lake. He came over that evening to visit. He spoke only Basque and Spanish, so our friend, who spoke Spanish, became the interpreter. He was young (early 30s?) and could not understand why our friend wasn't with a man. We kept expecting him to make a move on her, but he was very polite. That night, we slept surrounded by sheep, and, by the time the sun rose the next morning, they were gone. We stayed another night, but he didn't return.

Desfiles de los Niños - Fiestas de Santa Fe's Pet Parade

One of my favorite events of Fiestas de Santa Fe is Saturday morning's Desfile de los Niños, also known as the Pet Parade. Since the 1930s, kids have dressed up their pets and paraded around the Plaza. My father did it, I did it, and my children did it. From a kid's point of view, it's exciting to have perhaps your first moment in the spotlight, and from the adults point of view, it's the cutest thing ever. But participating is not without its' difficulties.

In 1952, my parents decided that it was our turn. Not satisfied with putting crepe paper flowers and a tutu on our dog, my dad found a burro that he rented for $20. My mom made my brother David and I little Mexican peon outfits, complete with sombreros. Mom later told me that she stayed up all Friday night finishing "the g-- d----- things." Saturday morning, we met the guy with the burro at the beginning of the parade and saddled up. The owner said that he would meet us at the end. It was really fun being the center of attention. For maybe a block. At that point, Señor Burro had had enough and came to a dead stop. With the parade backing up behind us, my dad and a friend of his tugged, pushed, cursed, and slapped him on the rump, to no avail. As the rest of the parade squeezed by us, I remember standing on the curb and realizing that our parade was over. That burro stayed right where he stopped until long after the parade had passed. His owner finally showed up, took up the halter rope, and led him docily away, Why my dad didn't have him stick around during the entire parade I never found out.

In the mid 1970s, we entered our daughters and our dog Sophie. This time it was much simpler - crepe paper flowers and a tutu. Unfortunately, this was the one year that the Fiesta Council decided to hold the parade in the afternoon rather than the morning. A half hour into the parade the pavement had gotton so hot that dogs were heading for any shade they could find and refusing to move. I ended up carrying Sophie for most of the route while my kids got to wave at the crowd.

It seems to be more fun watching the parade than participating in it. But, given the chance, I'd do it again in a heartbeat!